The July 30th edition of the New Yorker contained a truly (to me) spectacular profile of Bruce Springsteen (and I don’t particularly care for his music; mainly because I’m not particularly musical– but that’s another post.) Titled, “We are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two” by David Remnick, it contained the following quote:

The July 30th edition of the New Yorker contained a truly (to me) spectacular profile of Bruce Springsteen (and I don’t particularly care for his music; mainly because I’m not particularly musical– but that’s another post.) Titled, “We are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two” by David Remnick, it contained the following quote:

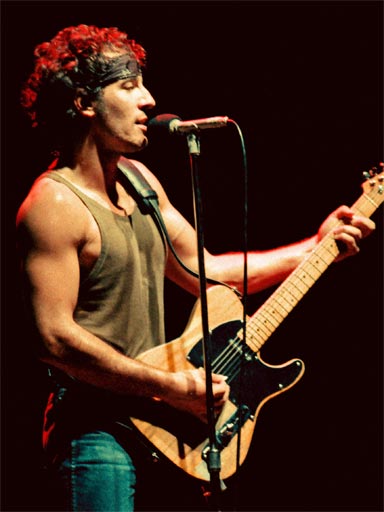

“Springsteen rehearses deliberately, working out all the spontaneous-seeming moves and postures: the solemn lowered head and raised fist, the hoisted talismanic Fender, the between-songs patter, the look of exultation in a single spotlight that he will enact in front of an audience. (“It’s theatre, you know,” he tells me later. I’m a theatrical performer.I’m whispering in your ear, and you’re dreaming my dreams, and then I’m getting a feeling for yours. I’ve been doing that for forty years.”) Springsteen has to do so much—lead the band, pace the show, sing, play guitar, command the audience, project to every corner of the hall, including the seats behind the stage—that to wing it completely is asking for disaster.”

I fell in love with that juxtaposition: the knowledge that performing is about an exchange of dreams AND an obscene amount of preparation.

Finding that balance is the key to success. Too often, however, I see speakers veer too heavily in one direction or another: choosing either to hope they establish a visceral connection with their audience, or spending so much time on the mechanics that they leave out the spirit.

For starters, hope is not a strategy. That said, too much strategy is a snore.

So what can you do?

As Bruce noted, begin by sharing your dreams—but have a feeling for the dreams of your audience. This is critical. The audience is not there to make your dreams come true. If anything, you are there to help them make theirs a reality. Let your inspiration become shared inspiration.

After that, rehearse, rehearse, rehearse. There’s no way around it.

Even for Bruce.

I look forward to your thoughts,

Frances Cole Jones